It has been a year since I trekked through Nuwaragala, what I fondly call a “rock full of secrets”. Yet, the memories from that journey remain startlingly vivid. I guess some adventures simply refuse to fade with time.

Nuwaragala belongs to the Gal Oya Mountain range, tucked deep in the hinterland of Ampara District, in Sri Lanka’s Eastern Province. The remnant mountain stands apart from the Island’s popular peaks. Here, you don’t find pilgrim queues like Adam’s Peak and overflowing tourists like Sigiriya. Nuwaragala holds its own history in silence and guards the stories of the Veddahs, Sri Lanka’s Indigenous people.

The Veddahs whisper tales of an ancient civilization that once thrived atop Nuwaragala, a time when kings are said to have sought refuge in the hidden hollows of the rock, and the Veddahs roamed freely through land they called their own. These stories also echo in the writings of R.L. Spittel, a Ceylonese physician and author who documented the region’s mysteries in his book Vanished Trails. Curious to relive fragments of that forgotten past, my friends and I braved the heat and rugged terrain to explore the ruins of the civilization swallowed by time.

Exploring Maha Oya

It was a sunny Friday morning in April when our group left Colombo at 6.30 a.m., heading east. After several hours on the road, we arrived at Blue Lake Ridge Hotel, one of the only lodgings in the area overlooking the tranquil Maha Oya Lake. Less polished than other destinations, Maha Oya had an air of underrated charm.

With the hike planned for next morning, we spent the rest of the afternoon exploring Maha Oya. We made our way to the Maha Oya reservoir, once part of an ancient irrigation system. Not far from there, we visited a natural hot spring known as Unuwathura Bubula, where locals still bathe as their ancestors did. As dusk painted the Maha Oya Lake in hues of orange and gold, we strolled along its edge, serenaded by birdsong and the gentle lapping of water.

Over dinner at the hotel, Sid, our seasoned expedition organiser entertained us with stories of his past treks, both petrifying and hilarious.

Meeting the Veddahs

The next morning began with a hearty Sri Lankan breakfast: steaming string hoppers, pol (coconut) sambol and lentil curry, fueling us for the 8 kilometer hike ahead. We set off by safari jeep to Pollebadda Veddah Village. There we met our guide, Nayaka Aththo (Chieftain) of Pollebadda, one of the few remaining Veddahs from the Pollebadda indigenous clan. Dressed in a checkered sarong and maroon shirt, he greeted us, clasping each of our hands warmly. Beside him stood Nayaka Aththo of Gal Oya and another clansman who were also going to accompany us on the trek.

We waited inside a mud hut-turned-museum to preserve our energy until the group was ready to begin the hike. The earthen walls displayed relics of Veddah life: bows and arrows, animal bones, cooking pots and hunting tools alongside a language chart translating animal names between Sinhala and the dwindling Veddah dialect. Time moved differently here.

The Nuwaragala Trek Begins

At exactly 9.57 a.m., we began the trek. The sun already bore down relentlessly, and the air was thick with humidity. Though we’d hoped for an earlier start to beat the heat, the Chieftains advised against it. Mornings, they said, belonged to the elephants. The Chieftains carried their wooden axes and their sacks clanked with pots, utensils and dry rations, ready to set up camp for the night; whereas, ours held only water, clothes and sleeping bags.

We picked our way through cowpea fields to get to the starting point of the trail. Then came our first obstacle: a knee-deep gentle stream we had to cross. Beyond it, an electric elephant fence sagged between posts, which didn’t seem to work to our luck. So much for elephant deterrents, I thought, as we scrambled onto a bulbous rock to regroup and catch our breath. Nayaka Aththo of Pollebadda, who led the way and seemed the most talkative of the group, warned us of potential elephant encounters and told us we needed to reach the Nuwaragala cave as quickly as possible.

From there, we entered a vast stretch of foliage. Thorny bushes clung to my clothes and tall grass towered over me. Every so often, we paused under trees to share shade and gulp water. Nayaka Aththo of Gal Oya walked barefoot on the heated rocky path, seemingly unaffected by discomfort. Watching him, I couldn’t help but wonder: had our modern comforts disconnected us from nature’s pulse?

Changing Landscapes

Two hours in, we noticed a change of scenery as we made our way through the scattered tall trees, their canopies allowing dagger-strokes of sunlight to pierce through. We stopped under the shade for a longer break, where Nayaka Aththo of Pollebadda set up a fire to boil water. Over cups of tea, we nibbled halapa and bananas; this was our lunch for the day. A few meters away, he pointed us to a weathered elephant skull; a clean deliberate hole marked where a bullet had ended its life a few years ago. The rest of its skeleton had long surrendered to the land, possibly washed away by monsoon streams.

As we continued to trek, the Chieftain kept us entertained, singing old kavi (folk poetry) with reverence and rhythm. His voice echoed through the trees, warning wildlife of our presence. Just as our stock of water had almost depleted, he veered off-trail to a tiny stream barely visible in the undergrowth, one of the few sources where we could refill our bottles.

I slipped off my shoes and dipped my aching feet into the cool water, sighing with relief! However, it was only a fleeting moment; with a clap of his worn hands, the Chieftain rallied us onward.

The Final Climb

By mid-afternoon, we reached the base of Nuwaragala. Here, Nayaka Aththo of Pollebadda snapped a small branch from a tree and offered a prayer for our safety — a gesture rooted in the Veddahs’ belief in animism. To them every tree, stone, rock and stream has its own spirit. I suddenly understood that invisible thread connecting all things. However many summits I’d climbed, none had ever asked me to acknowledge their soul first.

The remnant mountain majestically stood in front of us. The Chieftains mentioned how this now weathered rock was once a hideout of King Saddhatissa, the brother of the famed Sri Lankan King Dutugemunu. Saddhatissa sought refuge here almost 2,000 years ago, apparently evading his brother’s wrath until his eventual demise.

Then came the hard part…

The incline steepened, the path vanished and we were suddenly crawling; knees grinding against stone, fingernails clawing at crumbling earth. The heat grew oppressive. At one point, I collapsed onto a sun-warmed boulder, panting as the world spun slightly. No one spoke; only sounds of our laboured breaths and trees rustling in the wind.

Nuwaragala Cave

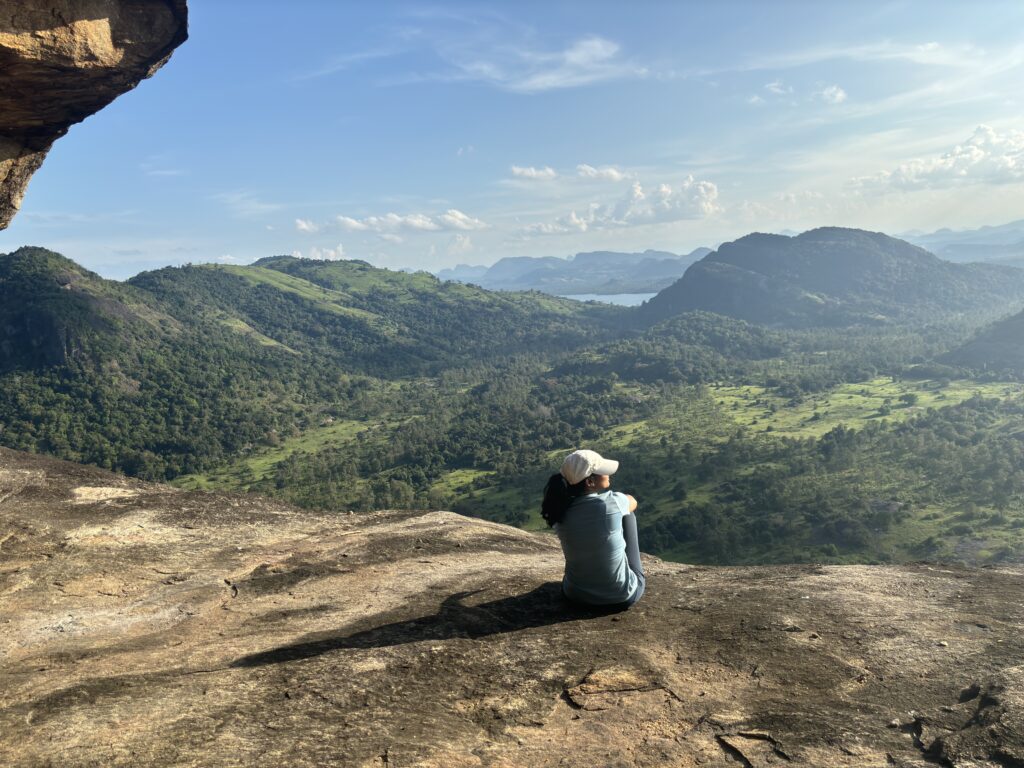

By about 4 p.m., we finally reached the massive Nuwaragala cave overlooking the mountain’s cliff. Everyone exhaled in quiet relief as we dropped our bags on the ground. This was where we were supposed to set camp for the night.

The overhanging cave bore traces of once-plastered walls, brickwork, decorative elements and inscriptions, though much has faded with time and is now scarred by graffiti left by travellers before us.

We stood there quietly, taking in the sweeping view from the cave. Soon, it was time to head out again, this time to freshen up before nightfall.

The Ancient Rock Pool

The trail gradually levelled out as we moved further up, and there it was. A 2,000-year-old infinity pool, emerged from the rock itself. How had this ancient pool, so ingeniously crafted, endured thousands of years without ever drying up? No pipes visible, no source explained; just pristine water, still obeying an unknown engineer’s long-forgotten design.

It is believed that this pool once served hundreds of meditating monks, as the site is thought to have been a monastery later built by King Lajjatissa, son of King Saddhatissa. Fresh elephant dung nearby suggested that today, it is a vital source of water for the creatures of the wild.

It was time to wash off the day’s dirt and grime. While some of the crew ventured further up to refill buckets from a hidden secret stream only known to the Veddahs, the rest of us waded into the frog-filled pool. I tried to ignore the slimy inhabitants as I slid in, but eventually, they scattered and gave way. The water felt cool, silty and alive. At one point, I attempted to touch the bottom of the pool with my toes, only to jerk back up when I felt nothing but murky grass.

The rest of the group soon joined us with buckets of water in hand, enough to keep us hydrated until the next day.

After changing into fresh clothes, I stood there in awe marvelling at the panoramic mountain views as the sunset smeared the sky in molten hues.

Camping Under the Stars

As night fell quickly, we debated whether to return to the cave or camp under the open sky. The lure of stargazing made the choice easy.

The Chieftains lit a fire and began preparing dinner. We joined in, chopping vegetables and stirring pots while sipping on hot chocolate. As we sat down on the bare rock with plates of rice, lentil curry and soy curry in hand, Nayaka Aththo of Pollebadda transported us through time, sharing tales of the vanished kingdom. There were once watchtowers, palaces and living quarters here, all now swallowed by trees and time. Even today, the remains of those ancient structures lie so scattered that it would be impossible to explore them in a single day.

Beneath the glistening stars, we unfurled our sleeping bags on the summit’s uneven rock. It was my first time sleeping under the open sky. Humid air clung to my skin as I wriggled into my sleeping bag. Lying back, we scanned the sky for shooting stars as they darted overhead. At one point, a frog landed on my forehead before leaping off, triggering a sharp screech and a brief moment of panic. While the Chieftains took turns as night watchers to keep an eye out for any elephant encounters, I kept sliding slowly down the rock’s slope all night. Sleep was elusive.

A Sunrise to Remember

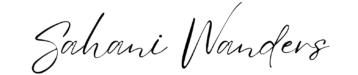

At dawn, the valley unfolded below us as the sunrise delicately painted the landscape.

We sat at the edge of the rock, gazing at vast caps of mountains stretched across the horizon while forests rolled into shadowed valleys. This land that once belonged to the Veddahs now stood as a conservation site. While the Chieftains sat nearby chewing their wad of betel, Sid quietly spoke of the challenges the Veddah community faced today. Hunting and gathering are now forbidden, threatening their ancestral way of life. Apart from small farming plots designated by the government, the Veddahs rely on government relief and tourism as a means of income for survival. With younger generations leaving for cities and education, only a handful of them remain to carry the legacy.

The Descent and Reflections

After eating a hearty breakfast of spicy chickpeas, lentil curry and pol roti with seeni sambol, we packed up for the descent as the morning sun climbed higher, already warming the surface.

Just as Nayaka Aththo of Pollebadda had greeted us with warmth the previous day, he thanked and blessed each of us in turn as we prepared to leave. My heart was full of gratitude.

On the way down, I noticed stone steps carved into the rock, along with impressive ramps and drainage gullies, all evidence of King Saddhatissa’s once-flourishing domain.

From a distance, Nuwaragala might seem like just another weathered rock, but it is full of secrets. Natural oppulance intertwines with historical mystery here. The trek, though exhausting, left me humbled and awestruck; and rich with lessons from the Veddah community and their deep connection to this land.

Nuwaragala cannot be trekked alone; visitors must request permission from the Maha Oya authorities, and the Chieftain of Pollebadda must guide the journey.

I hope that all who visit this majestic place carry their waste back & tread gently. Nuwaragala is a living history book, and one that deserves to be protected, honoured, and remembered.